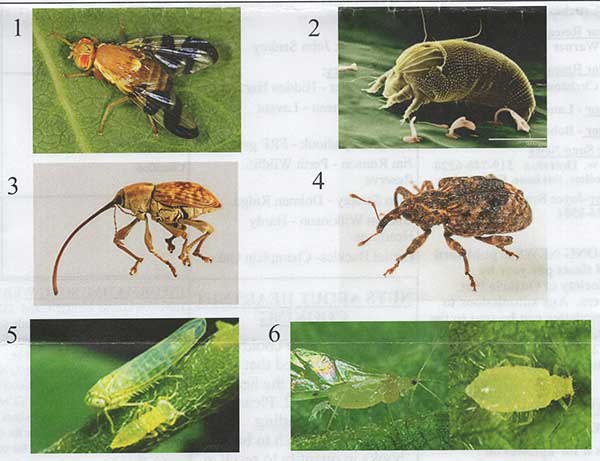

Do you know these pests of nut trees?

Not sure? Answers are at the bottom of this page.

This issue features these nut tree pests and solutions.

Do you know these pests of nut trees?

Not sure? Answers are at the bottom of this page.

This issue features these nut tree pests and solutions.

Is climate change real and are we humans responsible for it? Trump doesn't think so but science shows that over the past 50 years, the average global temperature has increased at the fastest rate in recorded history. And experts see the trend is accelerating: All but one of the 17 hottest years in NASA's 134-year record have occurred since 2000. In Canada the temperature rise is even more extreme than it is further south.

One cause is the rise in carbon dioxide emissions that are trapping the sun's reflected heat from the earth that normally would return to space. The heat is reflected back to earth much like a greenhouse cover reflects the sun's heat back into the greenhouse wanning it up. Our biggest producers of carbon dioxide are power plants and next are our transportation vehicles. Strides are being made to slow the warming but we are far from stopping it.

The effects are not only warming conditions but also more severe weather events. We can expect more tornadoes in areas where they seldom occur, more severe hurricanes, longer dry spells like the spring and summer of 2016, wetter spring and summers like 2017 and more wildfires like British Columbia is experiencing. Scientists in Prince Edward Island predict that within 50 years potatoes will not be a major crop in PEI because the climate is warming so fast. Hazelnuts could well be the next permanent crop for the island where the dryer warmer climate will match that of Maryland further south.

What can we do about it? It is well known that plants and trees absorb carbon dioxide and transform it into plant parts. Trees are the best at doing this because they remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it for long periods in the trunks, branches and roots. As nut growers, we can plant more nut trees to serve the additional purpose of producing a food product as well as storing carbon. As the climate warms, and our trees grow, our trees will sequester carbon at a faster rate. The warming climate will also allow us to grow nut trees further north, expanding the suitable areas for nut trees. Some growers are already anticipating this by planting trees that are not known to be hardy in their area.

There are cautions that we must take into account. We must be prepared for the long dry spells by having irrigation available. We also need to be aware that heavy rains with flooding can occur more frequently, so we need to have surface drainage patterns as well as under drain age in place. The future of nut growing is secure when we are prepared.

Butternut curculio (Conotrachelus juglandis) is an economically significant pest of black walnut, Persian (English) walnut, Japanese heartnut and butternut. There are two generations in Ontario.

The adults overwinter in ground litter under trees or weed areas. In the first generation both the adults and larvae cause injury to the tree and to the nut crop. The adults feed on tender twig terminals and leaf petioles in the early generation and the developing nuts causing an early nut drop. The larvae burrow into the nuts, inside young shoots, leaf petioles and stems. Larvae become full grown in four to five weeks and emerge from infested twigs and nuts in late July and August. Mature larvae enter directly into the soil to pupate.

The second generation of curculios emerges in late summer; feed on shoots, terminal growth and leaf petioles. They cut crescent shaped cavities in the developed nuts, usually close to the blossom end and lay eggs in the cavity. The eggs hatch and teed on the nut causing it to drop prematurely. The first generation lives until fall. The second generation pupates, then emerges to feed, finds cover in late fall as cold weather begins and completes the cycle.

'Surround' is the only product that is registered in Ontario for control. It may take several applications to cover the long season of activity. However, this pest seems to revolve in cycles where in some years it is problematic and others less so.

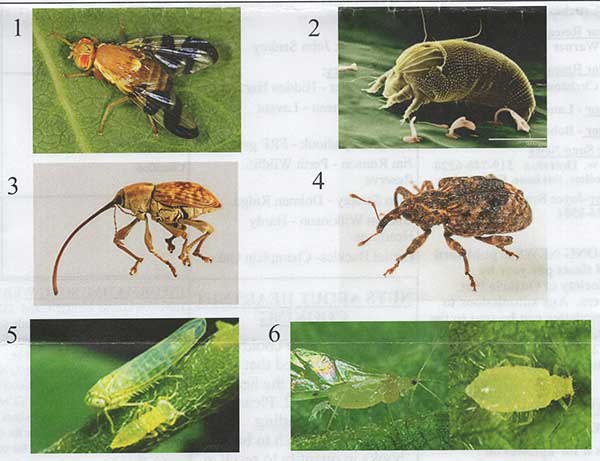

2016 is a year to remember for the walnut husk fly (Rhagoletis completa). It was a serious infection for the Persian walnut especially. It will lay its eggs in black walnut and heartnut husks but the larva does little or no harm to the nut meat. At the Grimo Nut Nursery one 'Matador EC 120' spray was applied in 2016 but it did not do the job and there was a considerable loss. Other local growers had complete losses. It was the worst year in recent memory. In 2017 three sprays at 2 weeks apart were used starting near the end of July.

The best way to determine if the flies have emerged from the ground and are active is to hang yellow sticky traps in the trees and observe when the flies are caught. When enough flies are present it is time to spray. An attractant like black strap molasses added to the spray tank will produce a better kill. The best place to buy a quantity of molasses is at a bulk food store. 'GF 720 Fruit Fly Baif is also registered but provides suppression. Only the lower branches need to be sprayed since the attractant will lead them there. Continue to use the traps until no more are caught and spray repeatedly until then.

Follow Publication 360 Tree Nuts guidelines available on the internet. The flies will begin laying eggs in mid to late August so it is important to spray in that time period. The adult husk fly is about the size of a housefly and very colorful. A yellowish white spot just below the area where the wings are attached and a dark triangular band at the tip of the wings distinguishes the husk fly from Other flies likely to be found in orchards.

Husk flies have one generation per year and overwinter as pupae in the soil. They emerge as adults from July until early September. Peak emergence is usually in mid-August. The female deposits eggs in groups of about 15 below the surface of the walnut husk near the stem. Eggs hatch into white maggots within 5 days. Older maggots are yellow with black mouth parts. After feeding on the husk for 3 to 5 weeks, mature maggots drop to the ground and burrow several inches into the soil to pupate. Most will emerge as adults the following summer but some remain in the soil for 2 years or longer.

Adult female husk flies can be distinguished from males by their slightly larger size. The walnut husk fly is a mid- to late season pest. It occurs in all walnut growing areas where black walnut is native. A husk fly infestation early in the season (late July to mid-August) leads to shriveled and darkened kernels or may induce mold growth. This damage may also be caused by other pests or environmental stresses. Late infestations do little damage to the kernels but may stain the shells making the nuts unattractive and unsalable.

Adults have characteristic wing bands and white spot. Walnut husk fly overwinters as a

pupa. Most pupae emerge as adults the following year, though some remain in the ground for 2

years, and a few even 3 or 4 years. Egg laying can begin anywhere from 2 to 6 weeks after adults

emerge. Yellow sticky traps used for fruit can be used for husk fly. Hang 6' up in a previously

infected tree.

The potato leafhopper (Empoascafabae) is a pest on many crops including some of our nut trees. This pest feeds on the leaves of sweet chestnut and Persian walnut in particular. When populations are numerous, feeding can result in distorted or dwarfed leaves, as with sweet chestnut and blackened leaf tips on Persian walnut. It can kill small branches and twigs. Newly transplanted trees are most susceptible to damage.

Adults are bright green, wedge-shaped and approximately 3 mm long. When at rest, the wings are held roof-like over the body. A row of six, small, round, white spots can also be seen on their backs, between the wings and head. Nymphs, which are of similar coloration, are wingless and smaller than the adults. When disturbed they often run sideways. Both adults and nymphs have piercing, sucking mouthparts. Eggs are approximately 1 mm long.

Potato Leafhopper adult

During the summer months this pest inhabits the eastern half of the United States and southern Canada. However, they do not survive in our northern winters. Adults must migrate northward annually from their overwintering sites in the Gulf States. Adults usually arrive in Ontario during May and remain throughout the warmer months. After mating, the female deposits 60 to 100 eggs over a 30-day period in veins or leaf stems of host plants. Nymphs hatch 6 to 9 days after oviposition and go through 5 developmental stages (instars) before becoming adults. Development takes approximately 20 days. Depending on temperatures and time of arrival, two or more generations can occur each year in Southern Ontario.

Adults and nymphs feed with piercing-sucking mouthparts on the sap of the host. This type of feeding results in phloem blockage within the plant. On chestnut and Persian walnut, the leaf margin may roll inward and turn brown or black. This weakening of the tree makes it more susceptible to winter injury.

Beneficial insects, such as green lacewings, lady beetles, and parasitic wasps can help to control this pest. Newly established chestnut, Persian walnut, hazelnut, hickory and pecan are susceptible to damage and need a spray of 'Admire' or 'Surround' to suppress them. In severe cases for bearing trees, refer to Publication 360, Tree Nuts for chemical control and timing.

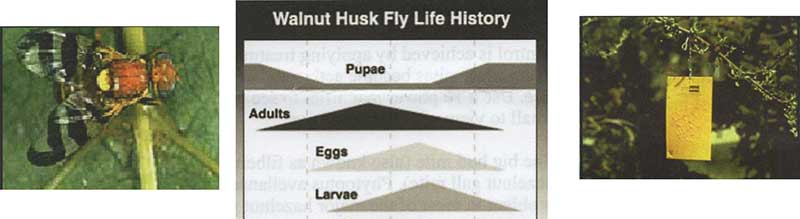

The filbert bud mite is a very small eriophyid mite that feeds on and within leaf and flower buds and catkins (male flowers) Feeding causes buds to swell to larger than normal size (hence the nickname "big bud mite"), and infested buds do not produce nuts. Cecidophyopsis vermiformis is another eriophyid mite also found in hazelnut orchards. Cecidophyopsis vermiformis feed in the enlarged buds created by the filbert bud mite; while their feeding does not cause big bud symptoms, it does cause further damage to the bud and, subsequently, yield loss.

Mite activity can be monitored by placing a sticky substance (Tanglefoot or double sided sticky tape) on twigs above and below buds that have evidence of mite infestation. Best control is achieved by applying treatments in the early spring when adult mites become active and are moving about the tree. Use a 10 power magnifier to see them since they are too small to view with the naked eye.

The big bud mite (also known as filbert bud mite and hazelnut gall mite), Phytoptus avellanae, is known to be a problem in most of the major hazelnut production areas around the world. This mite has long been associated with the formation of excessive large buds in hazelnuts. Specific plant damage is indicated by enlarged buds whereby infested terminal buds become swollen and deformed. Bud deformation also occurs in which the development of leaves, blossoms and fruits are affected.

Big bud mite infestation first becomes obvious during late summer and early autumn. Affected buds become spherical and swell to several times their normal size, reaching about 10 mm in diameter. These buds are prone to desiccation and fall from the tree prematurely). The big bud mite can affect both the vegetative and lower buds of hazelnut trees and seriously reducing the crop.

Big bud mites living within buds are protected from adverse conditions during the cold months of winter. However, they are subject to desiccation by warm, dry air when they start to migrate to new leaf buds during spring.

Refer to Publication 360 Tree Nuts for registered miticides. Apply when mites are detected in the sticky coating on the stems above the blasted buds. They can emerge over a 2-3 week period. If infestations are severe, two or three sprays may be needed targeting them in late April to late May. Spraying while they are in blasted buds or the new buds will not get them, so it is important to time the sprays.

Filbert bud mite magnified. Filbert bud mite damage is visible mid summer. S.voilen buds

as in 'b' are infested while in 'a' they are normal.Tight bud cultivars are resistant to entry of the

mites.

A blasted filbert bud produces no nuts

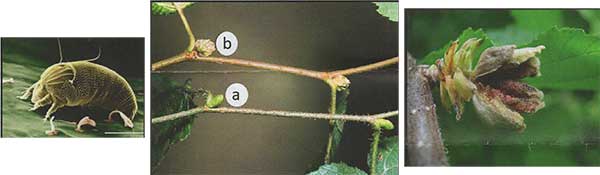

There are two aphids that affect hazelnuts. The first is the filbert aphid Myzocallis coryli. It is a medium to small size greenish aphid. The second is the hazelnut aphid Corylobium avellanae. It is a larger aphid. Both feed on the buds, leaves and husks. The exposed end of the nuts become tarnished and blackened by the honeydew created by the aphids.

Experimental evidence indicates that heavy infestations of aphids should be controlled. Damage caused by aphids is cumulative and will affect crop production and tree health. The benefits of control might not be seen during the first season of treatment but become evident after two years or more of aphid control.

The aphid overwinters as eggs on twigs. In early spring, eggs hatch, and the aphids feed on buds before moving to the leaves. The population can increase rapidly, and there are many generations per year. In the fall, sexual forms are produced which lay overwintering eggs.

For pest monitoring, the sampling period is April 1- Sept 30. Check three terminal branches per tree and three leaves per terminal. Count the number of aphids per leaf and treat when the following thresholds are reached: April: 20/leaf, May: 30/leaf, June: 40/leaf, and July: 40/leaf with an increasing population.

There is a natural parasitoid that lays its eggs in the aphid. This Turkish predator was imported to Oregon and has become well established there. Many orchards do not need to spray for this pest since the parasitoid became established. It is possible to introduce this parasitoid to Ontario to control this pest. This parsitoid does not cause any ill effects and its host is only the aphids that affect hazelnuts. If the parasitoid becomes established, treatment should be held off. Check back on population levels in a week. Mummified aphids indicate that the parasitoid is active. The mummies appear swollen, rounded and darker and may have an exit hole chewed by the wasp.

For chemical control, refer to Publication 360, Tree Nuts for the registered products to use and the proper timing for control.

Filbert aphid nymphs, Hazelnut aphid, Trioxyx pallidus

There are 2 species of native chestnut weevil that attack sweet chestnut, the 'lesser1 Curculio sayi and the 'greater,' and larger C. caryatrypes . Even though the life cycles are slightly different, the control methods are the same. Lesser and large chestnut weevils lay eggs on developing nuts. The larvae feed within the nut, compromising the kernel. Then they leave the nut, enter the ground and pupate.

If left unchecked, these weevils can infest and destroy the majority of nuts produced in an orchard. Recently there has been an upsurge of chestnut orchardists across Ontario reporting the occurrence of weevilled nuts. Once established control methods must be implemented.

Lesser chestnut weevil adults likely emerge from the soil during two separate periods, once in spring around bloom (June-July) and again in late summer-early fall just before burrs open (September-October) Weevils that emerge in the spring can be observed feeding on catkins. When the catkins decline, the population disappears. It is unknown if these spring weevils return to the soil or move off to feed on other plants. In September-October, a second wave of lesser chestnut weevils emerges. As burrs begin to open, the majority of egg-laying occurs for both the spring and fall emerging adult weevils.

Eggs are typically deposited in the downy lining surrounding the nut and hatch in approximately 3 0 days. The larvae feeds on the kernel and develops within the shell. After two to three weeks, larvae chew an exit hole in the nutshell and drop to the soil. The majority of the weevils will overwinter as larvae the first year, pupate in the soil the following fall and overwinter as adults. The total lifecycle is completed in two to three years.

Large chestnut weevil adults likely emerge in August or September and begin laying eggs in immature burrs almost immediately after emergence (well before lesser chestnut weevils begin laying eggs). Eggs hatch in five to seven days and the larvae feed and develop within the nut for two to three weeks before chewing a small exit hole and leaving the nut. The large chestnut weevil larvae usually exit the chestnut before the nuts drop to the ground and overwinter in the soil. Pupation and adult emergence takes place the following summer, a small population of larvae may overwinter a second winter before pupation. The total lifecycle is completed in one to two years.

To date there are no Publication 360 recommendations for the control of the chestnut weevil in Ontario. Contact Todd Leuty todd.3eutv@ontario.ca or Melanie Filotis melanie.fi!otas@ontario.ca if you have a weevil problem. For scouting and management ideas and techniques, please refer to: http://msue.anr.msu.edu/news/chestnut_weevil_a_potential_pest of_michigan_chestnuts

Chestnut weevil larvae & exit hole, Large chestnut weevil bvTodd Leuiy, Lesser chestnut

weevil adult

Other insect pests to look out for aside from the ones described in this newsletter include pests like scale insects, European red mite, walnut webworm, Japanese beetle, Gypsy moth, codling moth, spider mites, and dogwood borer. Thankfully not all of these need sprays every year. Most occasionally get out of hand when their natural predators can't keep up. Then it is up to us to help our with chemical controls.

Vertebrate pests also need attention and these include squirrels, raccoons, mice, moles, voles, chipmunks, deer, blue jays, and crows. Thankfully there are deterrents and predators for these as well.

Oregon Hazelnut Summer Meeting

Linda Grimo

I had the privilege of traveling with 6 Ontario farmers to the Oregon Grower's Society summer meeting in Albany, Oregon this month. We attended the meeting on August 2 and were hosted with private tours on August 3 at four different sites.

The Oregon Grower's meeting began at the Glaser farm where well over 600 attendees met. After the welcome and introductions the crowd was divided into four groups. Each group rotated to a different area in the Glaser farm to learn about the techniques that they implement at their 200+ acre farm.

The Glaser orchards provided an opportunity to actually see the results of a long history of chipping prunings. The second stop on the group rotation showed how the Glaser's have successfully managed drainage issues inherent in their terrain and they are one of the few who irrigate mature orchards. The third rotation discussed pruning techniques and the fourth was hazelnut pest control.

Following the Glaser presentations, we drove to the Linn County Expo Center for the rest of the day. There were more than 50 vendors showcasing a myriad of hazelnut oriented goods and services available to Oregon growers. The meeting included a fantastic lunch and the crowd had surged to 800 by the end of day.

The following day we first stopped at Shawn Mehlanbacher's hazelnut breeding station. He gave us a fantastic tour of the process of breeding hazelnuts.

Our second stop was to visit a grower who has been farming hazels for 50 years. His orchards are beautifully maintained and highly productive. He showed us the orchards and his amazing selection of harvesting equipment.

Our third tour was at the Christiansen farm where Jeff Newton, farm manager extraordinaire, showed us their processing operation. Neighbouring hazel farmers bring their freshly harvested hazels to be washed and dried until the processors are ready for them. This stop showed us a very practical approach to setting up similar operations in Ontario.

Our final stop of the day was to visit Willamette Processing plant. Here, they shell the nuts and sell them either in shell or shelled. They are farmers too and have beautiful young orchards with the newest cultivars as well as older mature orchards.

The growers and processors in Oregon were incredibly informative and provided a wealth of information to the six of us. This will help to build the hazelnut industry for Ontario.

Dr. Mehlenbacher explains the process of breeding hazelnuts at the University of Oregon

ECSONG Activities

Gord Wilkinson, Chair ECSONG

Long Sault Plantation

Gordon Wilkinson and John Adams were given a tour of the Long Sault nut

plantation by Murray Inch on May 16th. This plantation was established in 1993-94

by Ted Cormier with support from ECSONG, the Eastern Ontario Model Forest

and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. It is situated on an island in the St.

Lawrence River about 23 kilometres east of Cornwall. More details about this

plantation can be found in Murray's report published in the August 2010 issue of

ECSONG newsletter (see www.SQngonline.ca/ecsong/essavs/longsault2010.html).

Both grafted trees and seedlings of named varieties were planted at this site.

Documentation provided by Murray at the start of his tour and name tags, albeit

worn and difficult to read, helped us identify the nut tree varieties. The best

performing nut trees were the American chestnuts, black walnuts, buartnuts, and

shagbark hickories. The Persian walnuts were stunted, likely as a result of fairly

regular winter dieback. The heartnuts attained reasonable size but showed major

trunk scarring or limb dieback. None of the hazelnuts survived. The most exciting

discovery was a producing American chestnut tree over 25 feet tall showing no

sign of chestnut blight (see attached photo with Murray Inch and John Adams on

either side of this tree). We hope to return to this site next year with other ECSONG members for

more thorough brush

clearing, much needed tree tag replacement, and more detailed documentation of tree

performance.

Sault Nut Plantation American Chestnut

Lavant Shagbark Hickories

A mature, self-generating grove of about 1000 shagbark hickories is located on provincial

crown land on the French Line west of Brightside, Ontario at latitude 45°08'N (see

www.songonline.ca/ecsong/groves.html for more detail). Jim Ronson has been in regular contact

with Jordan Bemmels, a PhD student at the University of Michigan, who is conducting DNA

analysis on shagbark hickories in Eastern North America for his PhD thesis and for publication

and was willing to compare the genetic profile of our isolated Levant shagbark hickories with

those in other parts of Eastern North America. Soil analysis will also be carried out to determine

whether these trees are site specific. Given the uniqueness of this grove, ECSONG has been very

supportive and excited about Jordan's research work and will share the results when they are

finalized and ready to be released by the author. Jim has volunteered to help ECSONG pursue

provincial Conservation Reserve status for the shagbark hickories at this site.

Answers to page one nut tree pests: 1) walnut husk fly, 2) filbert bud mite, 3) chestnut curculio, 4) butternut curculio, 5) potato leafhopper, 6) filbert aphid

Provided by SONG. Feel free to copy with a credit.